The Melodic Conversation of How Bravery Triumphs Over Tragedy in Portrait of Courage: Gentileschi, Wiley, and the Story of Judith

by Yasmin Al-Omair-Nuncio

Art is always in conversation with other artworks, be it by simple references alone or by a direct response. I am a big fan of intertextuality, the almost Ouroboros approach to literary writings, and to think that art does not do the same would be doing a disservice to a lot of artists out there. With this way of thinking, one could connect everything together with just a few hops, skips, and jumps. Art exhibitions, or more specifically the curators of the exhibitions, help this through-line of artistic intertextuality blossom and yet I am still stunned by the sensational approach that the Portrait of Courage: Gentileschi, Wiley, and the Story of Judith takes which I saw at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston (MFAH) in March of this year.

Upon entry into the Caroline Wiess Law Building, one of the buildings a part of the MFAH, I was welcomed to the sight of two very different paintings placed across one another in the foyer of the building. This is not an unnatural occurrence, the MFAH has many artworks and different exhibitions that come through and yet there was something so striking when gazing upon this particular exhibition that graced the entrance of the Law Building. The exhibition, Portrait of Courage: Gentileschi, Wiley, and the Story of Judith, left me speechless. It is a traveling exhibition that was there at the MFAH for four months which featured two artworks of Judith Slaying Holofernes: a painting from the Baroque period by Artemisia Gentileschi and a contemporary painting by Kehinde Wiley. These two people, these two artists, are incredibly different but yet their artwork sang a harmonious tune together. Both of these artworks showcase a scene from the Old Testament story of Judith slaying Holofernes. The paintings are positioned across from each other, intending to converse with one another with the past looking to the present and the present reflecting on the past. What was particularly striking about the exhibition was the kinship between the two pieces despite their obvious physical differences. Not only that but the waves of time washed over me as well as let it seep through your pores. In short, the time between 1612 and 2012 is definitely vast and yet what speaks volumes in Wiley’s and Gentileschi’s artworks alike is how their depiction of Judith and Holofernes can relate to both the power men hold above women and the oppressive experiences that people of color face in the same way: courage has the power to triumph over tragedy.

If the title was stripped away from this exhibit, the theme of courage is still palpable enough that there is no way anyone would be able to miss it. The first painting my eyes fell upon was Gentileschi’s painting and it struck me immediately. I personally am a huge nerd when it comes to historical paintings, especially those around the Renaissance or Baroque period so I obviously gravitated to Gentileschi’s painting first. However, I do not doubt the idea that any and every viewer would be struck with this same gravitational pull to history as I did. When gazing upon a piece of history, not only did I develop a feeling of respect but I also felt as though I was conversing with the past just as much as the two paintings were conversing. I got to experience the feelings with the artist and imagine that I was looking at this painting with the artist, through time. Accompanying the exhibit was a statement and explanation of what the exhibition was showcasing, detailing a bit of history for both Gentileschi and Wiley. One thing that is brought up in relation to Gentileschi was how she was sexually assaulted by her mentor. Her version of the painting of Judith reflects the type of anger one would feel after such a terrible grievance. Judith in Gentileschi’s painting features two white women, Judith and her maidservant, both violent participants in this beheading of an also white Holoferenes. Both women show furrowed eyebrows, indicating a sense of concentration and justice. There is courage and power here and that courage is Gentileschi’s Judith being courageous enough to stand up against an oppressor. In the Old Testament story, Holofernes is a general for the Assyrians and his existence is detrimental to the Jewish people of Israel. Holofernes as well as Gentileschi’s assailant are both tormentors. Understanding the pain the artist has undergone elevates the painting and the feeling of justice hums in the air around the painting.

However, if one was to not know this history or the explanation was not provided by the exhibit, the painting speaks for itself when it comes to overcoming a great hardship. Even though Gentileschi’s figures are in the middle of taking off Holofernes head and not quite victorious in the action yet, we can see the effort in Judith’s hands. The grip Judith holds on the sword is one of familiarity and confidence while the grip she holds on Holofernes head is authoritative and equally confident. Continuously, the state of dress the women are in in comparison to Holofernes gives them more power. Where he is shirtless, presumably naked, the two women show no signs of any state of undress. Royal blue is the color chosen for Judith to wear, continuing that narrative of authority. Not only that but the women are in complementary colors, red and blue, furthering the idea of sisterhood and a shared idea of defeating the ones that have overpowered them before. While this is an inherently violent act, the beheading of a man, this is an act Judith must do not only for herself but for her people. Judith’s bravery speaks to the bravery oppressed individuals have to dawn in the face of oppression paired with the added context of Gentileschi’s background which speaks to the sisterhood between women who have experienced the horrors of sexual assault.

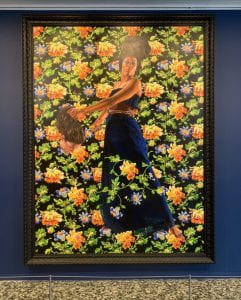

Across the way is a different triumph. Kehinde Wiley’s Judith is a black woman who has already cut off Holofernes’ head, the model of the head being a white woman. This Judith presumably did not have the helpful hand of her maidservant but rather committed this act of justice by herself. As a viewer, we are not witnessing the action like we are with Gentileschi’s work but instead we are witnessing a presentation: Judith has already slain Holofernes. Wiley’s Judith is both presenting the head as well as presenting herself. People of color have been historically left out of conversations in every field imaginable including something as expressive and freeing as the art world intends. Wiley lets the viewer know that black women are one of the most, if not the most, disrespected minority group while simultaneously being one of the most powerful. Continuously, the inclusion of a white woman being the model for Holofernes allows the viewer to sit back and understand that even in a world where women are disenfranchised by men, white women still benefit from the system, being an oppressor to people of color and therefore another version of Holofernes. More specifically, the painting reminds viewers that black women face oppression in a way that all women face in relation to the domineering male influence brought on by the patriarchy but also in the way that permeates the air no matter where in the world one may go.

When it comes to the actual content of the painting, Wiley mimics some aspects of Judith’s by putting his Judith in a similar royal blue color that Gentileschi’s dawns. This color decision connects the two in both power and the overarching theme of courage. Where the composition differs is that Wiley’s Judith is surrounded by floral tendrils that take over both the background and foreground with how they wrap around Judith herself. This conveys a connection to nature that Gentileschi’s Judith does not share. These tendrils draw the viewers all around the painting and with the floral vines coming across Judith’s legs lets the viewers’ eye glide up her torso and land on her triumphant face. Also, while Wiley’s Judith is not outwardly looking down on a viewer, the sheer size of the painting plus where it is placed on the wall makes a viewer look up at this woman in all her glory. I’m not a tall person at all but seeing this Judith in the process of swinging an iteration of Holofernes my direction made me feel even smaller yet not in a bad way. I felt like I was in the presence of a woman, a pure powerful being, that was overcoming and defeating the entity of despotism itself.

However, something important to note is that another difference between the two artists aside from time and race is that Kehinde Wiley is a man. Both of these paintings depict scenes of feminine power; a woman coming into her own and yet Wiley’s gender does not diminish this theme. While the patriarchy plays a part in all aspects of society and in the story of Judith and Holofernes itself, Wiley’s own experience with injustice speaks to Gentileschi’s and vice versa. Wiley is cognizant of the fact that women and men have different experiences when it comes to the patriarchal world we live in but due to his own brush with racism, he is able to sympathize extremely well with the story of Judith.

Where Gentileschi’s and Wiley’s paintings are most similar is through their rightful vindication: their courageous figures triumphing over tragedy. Gentileschi’s Judith is taking down a man who has wronged her and her community while Wiley’s Judith has overpowered the oppressor and stands tall with no room for shame. Wiley’s Judith speaks to black women’s history of prevailing despite their mistreatment by White America while Gentileschi’s Judith speaks to the unfortunately common atrocities men have inflicted upon women. These two paintings do indeed showcase courage but wherever courage is is also where the tragedy of pain lies as well. These women have been wronged, continually been wronged for more than 400 years and counting but neither of them are presented as victims. Women have been under the influence of men since the beginning of time but Gentileschi puts these two women above the man, taking back power that he has stolen. Wiley shares the same theme but builds on it by adding the context of having a black woman be the central Judith figure and a white woman representing Holofernes.

I encourage anyone who is able to catch this traveling exhibition to go and see Portrait of Courage: Gentileschi, Wiley, and the Story of Judith in person. Being caught in between the interconnected web of these two paintings, knowing that they are intended to speak to one another, feels like a symphony. What truly hammers in the aspect of courage triumphing over tragedy in both of these artworks is the fact that the themes of the paintings work in tandem with one another. While I would not be doing anyone any favors in equating misogyny to racism–because those issues are extremely different with varying degrees of severity–the vanquishing of both types of cruelty in the Judiths make for a melodic interaction. All in all, Artemisia Gentileschi and Kehinde Wiley paintings effortlessly harmonized with one another by cutting through time while providing a provocative dissonance through their different, yet similar, themes of overcoming their tragedy through the power of courage and bravery.

UP NEXT: YASMIN AL-OMAIR-NUNCIO AND VICTOR HUGO DE LUNA INTERVIEW